Data Note

August 2025

Caitlin Murphy, Feygele Jacobs, Marsha Regenstein

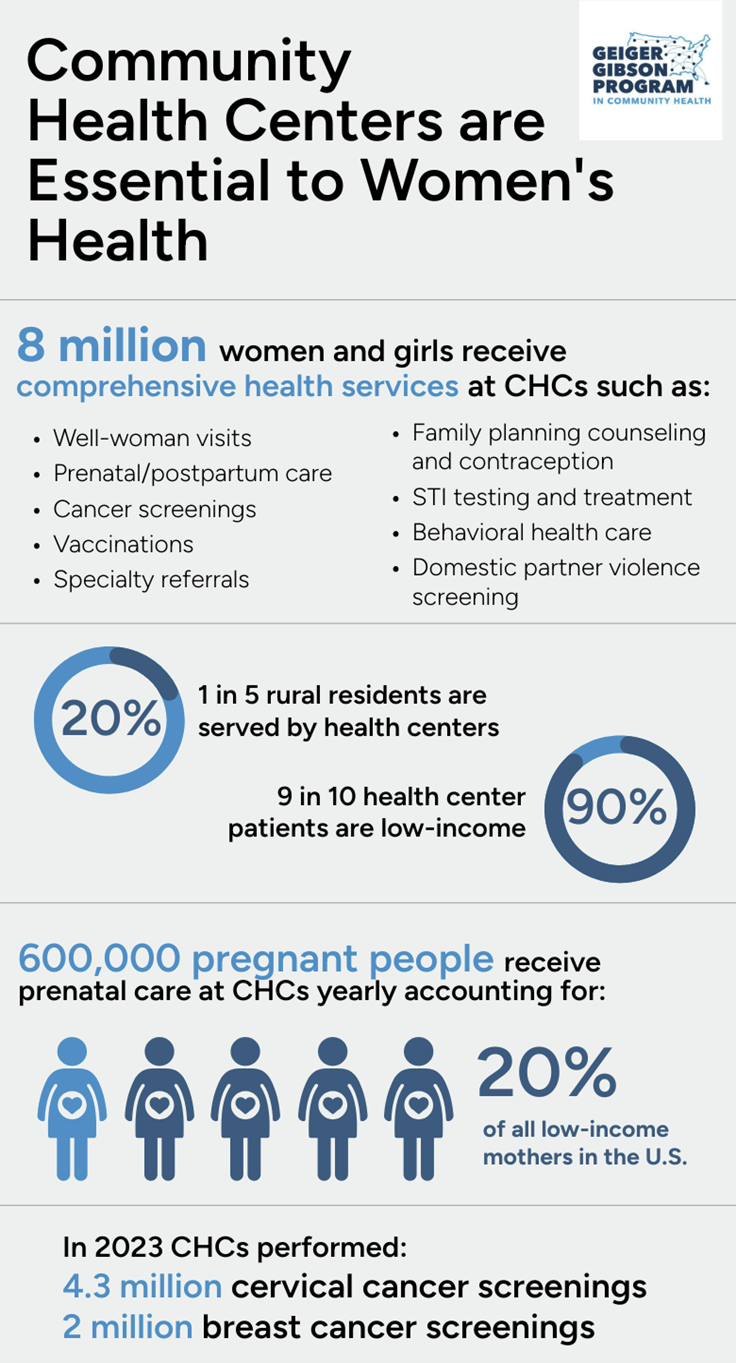

Community health centers (CHCs) are an essential source of health care for millions of U.S. women, building on a long history of providing care to under-resourced and higher-risk communities.

CHCs are the backbone of comprehensive, community-based care for women. Health centers provide women and their families with a broad range of primary and preventive care services - including well-woman visits, prenatal and perinatal care, and family planning services. In addition to preventive care and clinical services, health centers offer life-saving supportive services and case management, helping women and their families access healthy food,1 housing, legal aid,2 and more. In some states, more than 30% of women of reproductive age receive health care and supportive services at CHCs.3

Community health centers are an especially critical lifeline for low-income women, rural women, and women of color. Ninety percent of all patients served by CHCs are low-income,4[i]and 80% of CHC patients are either covered by public insurance like Medicaid or Medicare or are uninsured, illustrating how CHCs serve as a key provider of affordable, community-based care.5 Approximately 40% of CHCs are in rural communities, and one in five rural residents are served by health centers.6, 7 Over half (62%) of health center patients identify as members of a racial or ethnic minority group, including Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American.8

Health centers serve women of all ages, but are especially important in providing services for low-income reproductive-age women. Each year, more than 8 million women in their childbearing years rely on CHCs for health services, representing one in eight U.S. women ages 15-44 years old.9, 10 In 2024 alone, women of reproductive age made an estimated 6.1 million visits to health centers for maternal health and reproductive health services.11

This brief provides an overview of the essential, whole-person care CHCs provide to U.S. women. However, access to these services is under immense threat. The cuts included in the 2025 reconciliation legislation known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) will put enormous financial strain on CHCs’ ability to provide women’s health services. This strain could lead to CHCs across the county reducing services or closing12- further deepening maternity and contraceptive deserts and leaving under-resourced women and their families without care.

Well Woman Visits and Preventive Care

Health centers are a critical provider of well-woman visits, providing life-saving screening and preventive care. Recommended for all women ages 13 and above, annual well-woman visits include physical examinations, screenings, assessments of overall health and wellbeing, and guidance on various aspects of women's health.13 Well-woman visits may incorporate essential immunizations, cervical cancer and breast cancer screening, diabetes screening, mental health and substance use disorder screening, and vaccinations for the flu, HPV, and RSV.14 For adolescents, these visits are provided by pediatricians or family physicians who are specifically trained to care for patients throughout the life cycle.

Well woman visits are especially important for community health center patients, who are at higher risk than the general population.15 According to the most recent Health Center Patient Survey (HCPS),[ii] 24% of female health center patients were diagnosed with diabetes in the previous three years (compared to 10% nationwide) and 45% were informed they have high cholesterol (compared to approximately 10% nationwide).16, 17, 18, 19 When health centers identify conditions requiring specialty care unavailable onsite, they frequently assist patients in setting up appointments with outside providers. Health centers’ role in facilitating connections with specialty providers is a key difference between CHCs and typical primary care practices, and nearly 50% of female CHC patients report that they received support arranging services or medical appointments.20

Community health centers help low-income women overcome barriers to early cancer screening and treatment. Low-income women are at higher risk of death from preventable cancers such as cervical cancer and breast cancer because of obstacles to early screening, including transportation barriers, language barriers, and cost concerns.21, 22, 23 Health centers help female patients overcome hurdles to accessing these life-saving screenings: in 2023 alone, CHCs provided 4.3 million community-based cervical cancer screenings and 2 million breast cancer screenings.24

CHCs Provide Trusted and Supportive Women’s Healthcare: Women’s Health Navigators and Community Health Workers

Health centers have a long history of using patient navigators and community health workers (CHWs) to increase access to women’s preventive health services, including cervical cancer and breast cancer screening.25, 26 Patient navigators and CHWs provide trusted and supportive outreach, education, scheduling, referrals, and healthcare system navigation to help women receive recommended screenings and treatment.

Studies across diverse regions of the country – including Hawaii, Detroit, MI, the Pacific Northwest, and the U.S.-Mexico border - consistently find that these programs increase rates of women’s preventive screening, including breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening.27 For example, the Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center (WCCHC) used community health workers to run culturally-tailored “Kokua Groups” to provide education on the importance of cervical and breast cancer screening in traditional Native Hawaiian “talk story” fashion.28 Participants in Kokua Groups were more likely to receive breast cancer screening, cervical cancer screening, and encourage others to receive screening.

Maternity Care

Health centers provide communities with the full continuum of maternity services, including prenatal care, labor and delivery services, and postpartum care. Each year, over 600,000 pregnant patients, including approximately 115,000 women in rural communities, receive their prenatal care at a health center, representing 20% of all low-income mothers in the U.S.29, 30, 31, 32Likewise, over 170,000 deliveries are performed by CHC clinicians, representing 6% of all low-income babies.33, 34, 35, 36Health centers also provide an estimated half-million postpartum visits each year, providing essential medical check-ups, mental health screenings, and social supports to mothers following childbirth.37

Importantly, CHCs are a source of high-quality maternity care.38 Maternity outcomes at health centers are at or above the national average, despite serving lower-income and higher-risk patients. Over 70% of pregnant CHC patients access prenatal care in the first trimester.39 This early prenatal care is essential to prevent and minimize complications such as hypertension, anemia, infections, and gestational diabetes, which – when left untreated – can lead to preterm birth, low birth weight, and even death.40, 41CHCs deliver a lower percentage of low-weight infants compared to the national average (8% vs 10%), including among Black, Hispanic, and Asian infants generally at greater risk of low birth weight.42

Health centers provide supportive, whole-person services for mothers to help them care for their families. CHCs provide social and emotional supports in the form of doula services, group prenatal and parenting programs, connections to home visiting, and robust mental health programs. CHCs’ integrated care models ensure that maternal mental health services, including prenatal and postpartum screening and treatment, are readily available.43Importantly, CHCs are a trusted source of care – with 97% of patients saying they would recommend their CHC to friends and family.44

As obstetric departments and maternity hospitals close across the country, health centers have become increasingly essential to maternity care. Between 2010-2022, 500 hospitals closed their labor and delivery units, leaving most rural hospitals and more than a third of urban hospitals without obstetric care.45 Obstetric unit closures are linked to worsening birth outcomes. 46, 47Today, 35% of U.S. counties are classified as maternity care deserts, and CHCs often serve as the only – or one of the few – sources of maternal health care in these areas, highlighting their critical role.48 However, the maternity care burden on CHCs is expected to grow. The National Partnership for Women and Families estimates that 144 rural hospitals with labor and delivery units are at risk of closure or major service reductions due to OBBBA’s impending Medicaid cuts.49

CHCs Provide High-Quality, Comprehensive Maternity Care: Maternity Case Managers Provide “4th Trimester” Support at The CHC of Richmond

The Community Health Center of Richmond (CHCR) has been providing care for its communities in Staten Island, N.Y. for over two decades.50 As part of its comprehensive maternity care services, CHCR provides each maternity patient with a “maternity case manager” for the entirety of their pregnancy and postpartum journey.51 In addition to supporting all prenatal care and needs, maternity case managers place a special emphasis on ensuring that moms are prepared for and supported during the postpartum “fourth trimester” – the critically important three-month period after delivery when moms and newborns need to stay in close touch with their health care providers.52

Before birth, case managers and maternity patients co-create a “postpartum care plan” to ensure that new mothers have the support they need. This includes planning for at least two postpartum clinic visits, setting up weekly postpartum check-ins with doulas, and addressing any barriers mom may encounter to accessing care, such as transportation barriers.53

Family Planning and Contraception Services

Health centers provide comprehensive family planning services, including life-saving testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Undetected and untreated STIs can result in cancer risk, chronic pain, infertility, pregnancy complications, and even infant death.54, 55 These infections disproportionally impact low-income and persons of color, illustrating the importance of CHCs in detecting and treating STIs.56 In 2023, CHCs screened 3.5 million women and men for HIV and treated over 300,000 cases of STIs.57, 58

CHCs are an important source of contraceptive counseling and methods. Most health centers offer the full range of contraceptive methods, including short-acting methods like birth control pills and long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) such as intrauterine devices/IUDs and implants.59 Access to these services is especially important for low-income women, who encounter greater barriers to obtaining contraceptives and are at greater risk of unintended pregnancy.60 Unintended pregnancies can place women at greater risk for preterm birth and other pregnancy complications due to delayed entry into prenatal care.61, 62, 63 In 2023, CHCs provided contraceptive care to nearly 1.7 million patients.64

As contraceptive deserts deepen, CHCs are becoming an increasingly important source of family planning care. In recent years, health centers have been reporting increased demand for contraceptive care – especially for highly effective forms of contraception such as IUDs and implants.65 This increased demand has likely resulted from increasingly limited access to comprehensive reproductive health and deepening contraception deserts, which will only worsen if federal efforts cutting resources to Planned Parenthood and other women’s health providers persist.66, 67 CHCs’ ability to meet increasing contraceptive demand is threatened by cuts to their own funding, including cuts to Medicaid, uncertainty about the Community Health Center Fund (due to expire on September 30, 2025), and in some cases, cuts to Title X grants.68

Addressing Social Risk Among Women and Families

Health centers regularly screen for women’s social risk to improve overall health and wellbeing. CHCs recognize that socioeconomic factors such as poverty, employment, and education may impact as much as 50% of health outcomes.69 From their earliest days, health centers have been designed to address social factors, and regularly screen for social need and related risks that impact women’s and families’ health, such as food insecurity, housing instability, legal issues, and transportation needs.70, 71 Nearly three-quarters of all health centers screen for social risk factors, while an additional 23% report they are planning to collect this information.72

CHCs help facilitate access to needed social supports. Many health centers provide support on-site to address identified social needs. A 2021 nationwide survey of health centers found that 42% offered services such as a food pantry or meal delivery service, and 63% provided transportation services.73 Health centers are also increasingly embedding medical-legal partnerships (MLPs), which provide legal intervention to address challenges related to housing, education, family law, public benefits, immigration status, veterans’ benefits, and other individual and community-level needs.74 When services aren’t available on-site, health centers provide direct referrals and warm hand-offs to community-based organizations.

Women’s Health Services at CHCs are Under Immense Threat

Community health centers provide high-quality health services to all members of their community, but are an especially important access point for low-income women, rural women, and women of color. Yet health centers are increasingly operating in the red, with limited resources. Shrinking federal funding, increased costs, and rising service demand driven by maternity and contraceptive deserts have created immense operational and fiscal strain on CHCs.75, 76, 77

New policy changes introduced by the Administration in 2025 broaden and deepen the pressure on CHCs, undermining their ability to offer comprehensive women’s health services. Several CHCs, especially in rural areas, have started to reduce operations and close sites because of these new policies.78

Among the key policy issues are:

- $1 trillion in federal cuts to Medicaid and the ACA Marketplace.79Millions of CHC patients are expected to lose Medicaid and Marketplace coverage as a result of OBBBA.80 This coverage loss will cost health centers billions in revenue, and could result in major staffing cuts, including reductions in the number of doctors, nurse practitioners, behavioral health specialists, and other personnel.81 Simultaneously, Medicaid cuts will put hospitals at risk for closure, with nearly 150 rural hospitals with labor and delivery units susceptible to closure or severe cutbacks due to Medicaid cuts.82 Hospital closures, especially in rural areas, will drive additional patients to health centers and put further stress on CHC operations.

- Congressional funding for community health centers is set to expire in September 2025. The Community Health Center Fund (CHCF), which provides 70% of federal health center grant funding, must be periodically reauthorized by Congress.83With the future of the CHCF in the balance, CHCs face uncertainty and financial instability, which could force hiring freezes and service reductions.84

- Proposed elimination of funding for Title X family planning grants. Title X grants currently provide nearly 4,000 U.S. clinical sites with funds to make family planning available to low-income and uninsured patients.85 Approximately one-quarter of these clinic sites were operated by health centers, which rely on these additional funds to make the full range of contraceptive services available, including long-acting options such as IUDs and implants.86 Elimination of federal Title X funding would erode the ability of many health centers to stay fully stocked on contraceptive methods and provide family planning care.

- Proposed elimination of federal funds for Planned Parenthood clinics. Planned Parenthood clinics across the US may need to shutter if they are refused federal Medicaid funding. These closures will leave massive service gaps in preventive services, family planning, STI/STD care, and other services. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that CHCs would need to absorb an additional one million contraceptive clients nationally to fill gaps left by Planned Parenthood closures. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that CHCs would need to absorb an additional one million contraceptive clients nationally to fill gaps left by Planned Parenthood The Guttmacher Institute estimates that CHCs would need to absorb an additional one million contraceptive clients nationally to fill gaps left by Planned Parenthood closures.87 While CHCs are an essential source of care, they have neither the funds nor capacity to fill these gaps, especially as they lose funding themselves.

These major policy shifts deeply threaten CHCs’ ability to provide trusted and life-saving care to one in eight U.S. women, including well-woman visits, maternity care, cancer screenings, immunizations, family planning care, and supportive services. Multiple and rapid supports are needed to protect these services for our most under-resourced, low-income, and rural women and families. Robust federal health center funding is essential to keep CHCs operating. In addition, state and federal actions are needed to offset the impacts that deep cuts to Medicaid and other vital programs will have on health centers.

Notes

[i] “Low income” is defined as households earning 200% or less of the federal poverty level (FPL). In 2023, this was equivalent to a household income of $49,720 for a family of three.

[ii] The Health Center Patient Survey (HCPS) is a patient-reported survey periodically conducted for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to capture CHC patient needs and experiences. The most recent survey was conducted in 2002.

- 1Regenstein, M., Jacobs, F., & Nketiah, L. (2025). Community Health Centers: A Six-Decade Commitment to Nutrition and Health. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/community-health-centers-six-decade-commitment-nutrition-and-health

- 2Regenstein, M. (2025). Helping Patients Navigate Healthier Lives through Legal Interventions: Medical-Legal Partnerships in Community Health Centers. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/helping-patients-navigate-healthier-lives-through-legal-interventions-medical-legal-partnerships

- 3HRSA Data Warehouse. (2023). 2023 Health Center Data. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national

- 4HRSA Data Warehouse. (2023). 2023 Health Center Data. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national

- 5Pillai, A., Corallo, B., & Tolbert, J. (2025). Community Health Center Patients, Financing, and Services. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-center-patients-financing-and-services/

- 6National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2024). America’s Health Centers: By the Numbers. https://www.nachc.org/resource/americas-health-centers-by-the-numbers/

- 7Pillai, A., Corallo, B., & Tolbert, J. (2025). Community Health Center Patients, Financing, and Services. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-center-patients-financing-and-services/

- 8Pillai, A., Corallo, B., & Tolbert, J. (2025). Community Health Center Patients, Financing, and Services. The Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-center-patients-financing-and-services/

- 9 HRSA Data Warehouse. (2023). 2023 Health Center Data. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national

- 10 March of Dimes. (2024). Peristats: Women 15-44 years below federal poverty level: US, 2021-2023 Average. https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99&top=14&stop=159&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1

- 11CDC. (2025). Preliminary Estimates of Visits to Health Centers in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/prelim-hc-visits/index.htm

- 12National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). NACHC Statement on House Passage of the “One Big Beautiful Bill”. https://www.nachc.org/nachc-statement-on-house-passage-of-the-one-big-beautiful-bill/

- 13Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). (2025). Well-Woman Chart. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wellwomanchart/

- 14Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). (2025). Well-Woman Chart. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wellwomanchart/

- 15HRSA. (2024). Impact of the Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-center-program/impact-health-center-program

- 16CDC. (2024). High Cholesterol Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

- 17CDC. (2023). QuickStats: Percentage of Adults Aged ≥18 Years Who Took Prescription Medication During the Past 12 Months, by Sex and Age Group — National Health Interview Survey, United States, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7216a7

- 18Baumblatt, J., Fryar, C., Gu, Q., & Ashman, J. (2024). Prevalence of Total, Diagnosed, and Undiagnosed Diabetes in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. NCHS Data Brief 516. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/165794.

- 19HRSA Data Warehouse. (2022). 2022 Health Center Patient Survey Dashboard. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-centers/hcps/dashboard-2022#/topic

- 20HRSA Data Warehouse. (2022). 2022 Health Center Patient Survey Dashboard. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-centers/hcps/dashboard-2022#/topic

- 21Amboree, T. L. et al. (2024). Recent trends in cervical cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, and mortality according to county‐level income in the United States, 2000–2019. International journal of cancer. 154(9): 1549-1555.

- 22Lobb, R., Ayanian, J. Z., Allen, J. D., & Emmons, K. M. (2010). Stage of breast cancer at diagnosis among low‐income women with access to mammography. Cancer. 116(23): 5487-5496.

- 23Susan G. Komen Foundation. (2025). How Do Breast Cancer Screening Rates Compare Among Different Groups in the US? https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/screening/screening-disparities/

- 24HRSA. (2024). Impact of the Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-center-program/impact-health-center-program

- 25Roland, K. B. et al. (2017). Use of Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Improve Cancer Outcomes Among Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Systematic Literature Review. Health equity. 1(1): 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2017.0001

- 26Attipoe-Dorcoo, S., Chattopadhyay, S. K., Verughese, J., Ekwueme, D. U., Sabatino, S. A., Peng, Y., & Community Preventive Services Task Force (2021). Engaging Community Health Workers to Increase Cancer Screening: A Community Guide Systematic Economic Review. American journal of preventive medicine. 60(4): e189–e197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.011

- 27Roland, K. B. et al. (2017). Use of Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Improve Cancer Outcomes Among Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Systematic Literature Review. Health equity. 1(1): 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2017.0001

- 28Gotay, C. C. et al. (2000). Impact of a culturally appropriate intervention on breast and cervical screening among native Hawaiian women. Preventive medicine. 31(5), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2000.0732

- 29Shin, P., Rosenbaum, S. Morris, R., Johnson, K., Jacobs, F. (2022). In the Take of Dobbs, are CHCs Prepared to Respond to Rising Maternal and Infant Care Needs? The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs4421/files/2022-07/gg-rchn-wake-of-dobbs-format-071722-final-x-remediated-tc_0.pdf

- 30 National Center for Health Statistics. (2025). Preliminary Estimates of Visits to Health Centers in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/prelim-hc-visits/index.htm

- 31National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). 2025 Uniform Data System Chartbook: Analysis of the 2023 UDS Data. https://www.nachc.org/resource/2025-uniform-data-system-chartbook-analysis-of-the-2023-uds-data/

- 32Census. (2023). 2023 American Community Survey Estimates. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S1301?q=S1301:+Fertility

- 33Shin, P., Rosenbaum, S. Morris, R., Johnson, K., Jacobs, F. (2022). In the Take of Dobbs, are CHCs Prepared to Respond to Rising Maternal and Infant Care Needs? The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs4421/files/2022-07/gg-rchn-wake-of-dobbs-format-071722-final-x-remediated-tc_0.pdf

- 34 National Center for Health Statistics. (2025). Preliminary Estimates of Visits to Health Centers in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/prelim-hc-visits/index.htm

- 35National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). 2025 Uniform Data System Chartbook: Analysis of the 2023 UDS Data. https://www.nachc.org/resource/2025-uniform-data-system-chartbook-analysis-of-the-2023-uds-data/

- 36Census. (2023). 2023 American Community Survey Estimates. https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S1301?q=S1301:+Fertility

- 37HRSA. (2024). Impact of the Health Center Program. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-center-program/impact-health-center-program

- 38Advocates for Community Health. (2025). Federally Qualified Health Centers Are Central to Addressing the US Maternal Health Crisis. https://advocatesforcommunityhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/2025-Maternal-Health-White-Paper.pdf

- 39National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). 2025 Uniform Data System Chartbook: Analysis of the 2023 UDS Data. https://www.nachc.org/resource/2025-uniform-data-system-chartbook-analysis-of-the-2023-uds-data/

- 40NIH. (2017). What is prenatal care and why is it important? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pregnancy/conditioninfo/prenatal-care

- 41National Council of State Legislators. (2025). State Approaches to Ensuring Healthy Pregnancies Through Prenatal Care. https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-approaches-to-ensuring-healthy-pregnancies-through-prenatal-care

- 42National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2024). Community Health Centers: Providers, Partners, and Employers of Choice – 2024 Chartbook. https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Community-Health-Center-Chartbook-2023-2021UDS.pdf

- 43Advocates for Community Health. (2025). Federally Qualified Health Centers Are Central to Addressing the US Maternal Health Crisis. https://advocatesforcommunityhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/2025-Maternal-Health-White-Paper.pdf

- 44HRSA Data Warehouse. (2022). 2022 Health Center Patient Survey Dashboard. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-centers/hcps/dashboard-2022#/topic

- 45 Kliff, S. (2024, December 4). Most rural hospitals have closed their maternity wards, study finds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/04/health/maternity-wards-closing.html

- 46Kozhimannil, K. B., Hung, P., Henning-Smith, C., Casey, M. M., & Prasad, S. (2018). Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States. JAMA, 319(12), 1239–1247. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.1830

- 47March of Dimes. (2024). Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US. https://www.marchofdimes.org/maternity-care-deserts-report

- 48Markus AR, Pillai D. Mapping the Location of Health Centers in Relation to "Maternity Care Deserts": Associations With Utilization of Women's Health Providers and Services. Med Care. 2021 Oct 1;59(Suppl 5):S434-S440. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001611

- 49Donelson, R., Eng, M., & Guerra, M. (2025). Republican Budget Bill Could Close over 140 Rural Labor and Delivery Units. The National Partnership for Women and Families. https://nationalpartnership.org/report/republican-budget-bill-could-close-over-140-rural-labor-and-delivery-units/

- 50The Community Health Center of Richmond. (2025.) About. https://chcrichmond.org/

- 51The Community Health Center of Richmond. (2024). A Guide to Your Pregnancy. https://chcrichmond.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/CHCR_PregnancyBrochure-8.5x11_v11.pdf

- 52Shoreline Health Solutions. (2024). Community Health Center of Richmond. https://www.shorelinehealthsolutions.com/community-health-center-of-richmond/

- 53Shoreline Health Solutions. (2024). Community Health Center of Richmond. https://www.shorelinehealthsolutions.com/community-health-center-of-richmond/

- 54CDC. (2023). Sexually Transmitted Diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/std/general/default.htm

- 55Barry-Jester, A. (2022). Babies Die as Congenital Syphilis Continues a Decade-Long Surge Across the US. Kaiser Family Foundation Health News. https://khn.org/news/article/babies-die-as-congenital-syphilis-continues-a-decade-long-surge-across-the-us

- 56Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2020). Women's preventive services guidelines. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573159/

- 57National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). 2025 Uniform Data System Chartbook: Analysis of the 2023 UDS Data. https://www.nachc.org/resource/2025-uniform-data-system-chartbook-analysis-of-the-2023-uds-data/

- 58National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). 2025 Uniform Data System Chartbook: Analysis of the 2023 UDS Data. https://www.nachc.org/resource/2025-uniform-data-system-chartbook-analysis-of-the-2023-uds-data/

- 59Wood, S. et al. (2018). Community Health Centers and Family Planning in an Era of Policy Uncertainty. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/community-health-centers-and-family-planning-in-an-era-of-policy-uncertainty

- 60The Guttmacher Institute. (2019). Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/fb-unintended-pregnancy-us.pdf

- 61Gemmill A, Lindberg LD. Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jul;122(1):64-71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182955e58

- 62Rice, L. W., Espey, E., Fenner, D. E., Gregory, K. D., Askins, J., & Lockwood, C. J. (2020). Universal access to contraception: women, families, and communities benefit. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 222(2), 150.e1–150.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.014

- 63Conde-Agudelo, A., Rosas-Bermúdez, A., & Kafury-Goeta, A. C. (2006). Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 295(15), 1809–1823. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.15.1809

- 64HRSA Data Warehouse. (2023). 2023 Health Center Data. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national

- 65Murphy, C., Shin, P., Jacobs, F., & Johnson, K. (2024). In States with Abortion Bans, CHC Patients Face Challenges Getting Reproductive Health Care. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2024/states-abortion-bans-community-health-center-patients-face-challenges-getting

- 66Sobel, Laurie & Salganicoff, A. (2025). SCOTUS Ruling on Medina v. Planned Parenthood Will Limit Access to Care for Patients in South Carolina and Beyond. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/scotus-ruling-on-medina-v-planned-parenthood-will-limit-access-to-care-for-patients-in-south-carolina-and-beyond/

- 67Frederiksen, B., Gomez, I., & Salganicoff, A. (2025). The Impact of Medicaid and Title X on Planned Parenthood. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-impact-of-medicaid-and-title-x-on-planned-parenthood/

- 68Frederiksen, B., Gomez, I., & Salganicoff, A. (2025). Title X Grantees and Clinics Affected by the Trump Administration’s Funding Freeze. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/title-x-grantees-and-clinics-affected-by-the-trump-administrations-funding-freeze/

- 69Whitman, A. et al. (2022). Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf

- 70Shin, P., Sharac, J., Jacobs, F., Rosenbaum, S. (2022). Three in Four CHCs Are Engaged in SDH Activities. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/three-four-community-health-centers-are-engaged-social-determinants-health-activities-making-these

- 71Stevens, D. M., Melinkovich, P., & Jacobs, F. (2022). Beyond Primary Care: Renewing the Community Health Center Vision for Today's Health Crisis. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 33(2): 1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2022.0086

- 72Shin, P., Sharac, J., Jacobs, F., Rosenbaum, S. (2022). Three in Four CHCs Are Engaged in SDH Activities. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/three-four-community-health-centers-are-engaged-social-determinants-health-activities-making-these

- 73Sharac, J., Stolyar, L., Corallo, B., Tolbert, J., Shin, P., and Rosenbaum, S. (2022). How Community Health Centers Are Serving Low-Income Communities During the COVID-19 Pandemic Amid New and Continuing Challenges. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-community-health-centers-are-serving-low-income-communities-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-amid-new-and-continuing-challenges/

- 74Regenstein, M. (2025). Helping Patients Navigate Healthier Lives through Legal Interventions: Medical-Legal Partnerships in Community Health Centers. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/helping-patients-navigate-healthier-lives-through-legal-interventions-medical-legal-partnerships

- 75Kwon, K, Nketiah, L, Jacobs, F, Rosenbaum, S, and Ku, L. (2024). Policy Issues Brief #72: Community Health Centers Grew Through 2023, But Serious Hazards Are on the Horizon. The Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. https://geigergibson.publichealth.gwu.edu/72-community-health-centers-grew-through-2023-serious-hazards-are-horizon

- 76Murphy, C., Shin, P., Jacobs, F., & Johnson, K. (2024). In States with Abortion Bans, CHC Patients Face Challenges Getting Reproductive Health Care. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2024/states-abortion-bans-community-health-center-patients-face-challenges-getting

- 77Murphy, C., Johnson, K., Jacobs, F., Shin, P. (2024). Stressors Stack Up on Essential Maternity Providers – CHCs Need Support in a Post-Dobbs World. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2024/stressors-stack-essential-maternity-providers-community-health-centers-need-support-post

- 78The Boston Globe. (August 8, 2025). Trump’s Medicaid Cuts Deal a Damaging Blow to FQHCs. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/08/10/metro/trump-medicaid-cuts-health-centers-closing-new-hampshire/

- 79Congressional Budget Office. (2025). Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, relative to CBO’s January 2025 baseline. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61534

- 80Rosenbaum, S., Jacobs, F., Johnson, K. (2025). Nearly 5.6 Millon CHC Patients Could Lose Medicaid Coverage Under New Work Requirements, with Revenue Losses up to $32 Billion. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2025/community-health-center-patients-medicaid-coverage-work-requirements

- 81National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). NACHC Statement on House Passage of the “One Big Beautiful Bill”. https://www.nachc.org/nachc-statement-on-house-passage-of-the-one-big-beautiful-bill/

- 82Donelson, R., Eng, M., & Guerra, M. (2025). Republican Budget Bill Could Close over 140 Rural Labor and Delivery Units. The National Partnership for Women and Families. https://nationalpartnership.org/report/republican-budget-bill-could-close-over-140-rural-labor-and-delivery-units/

- 83National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). Health Center Funding. https://www.nachc.org/policy-advocacy/policy-priorities/health-center-funding/

- 84National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). (2025). Health Center Funding. https://www.nachc.org/policy-advocacy/policy-priorities/health-center-funding/

- 85Frederiksen, B., Gomez, I., & Salganicoff, A. (2025). Title X Grantees and Clinics Affected by the Trump Administration’s Funding Freeze. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/title-x-grantees-and-clinics-affected-by-the-trump-administrations-funding-freeze/

- 86Frederiksen, B., Gomez, I., & Salganicoff, A. (2025). Title X Grantees and Clinics Affected by the Trump Administration’s Funding Freeze. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/title-x-grantees-and-clinics-affected-by-the-trump-administrations-funding-freeze/

- 87The Guttmacher Institute. (2025). Federally Qualified Health Centers Could Not Readily Replace Planned Parenthood. https://www.guttmacher.org/news-release/2025/federally-qualified-health-centers-could-not-readily-replace-planned-parenthood