Leighton Ku, Jordan Herring, and Feygele Jacobs

September 2025

A new research report published on September 5, 2025 in the JAMA Health Forum, demonstrates how community health centers (also called federally qualified health centers or FQHCs) step up to provide care in America’s most disadvantaged communities.

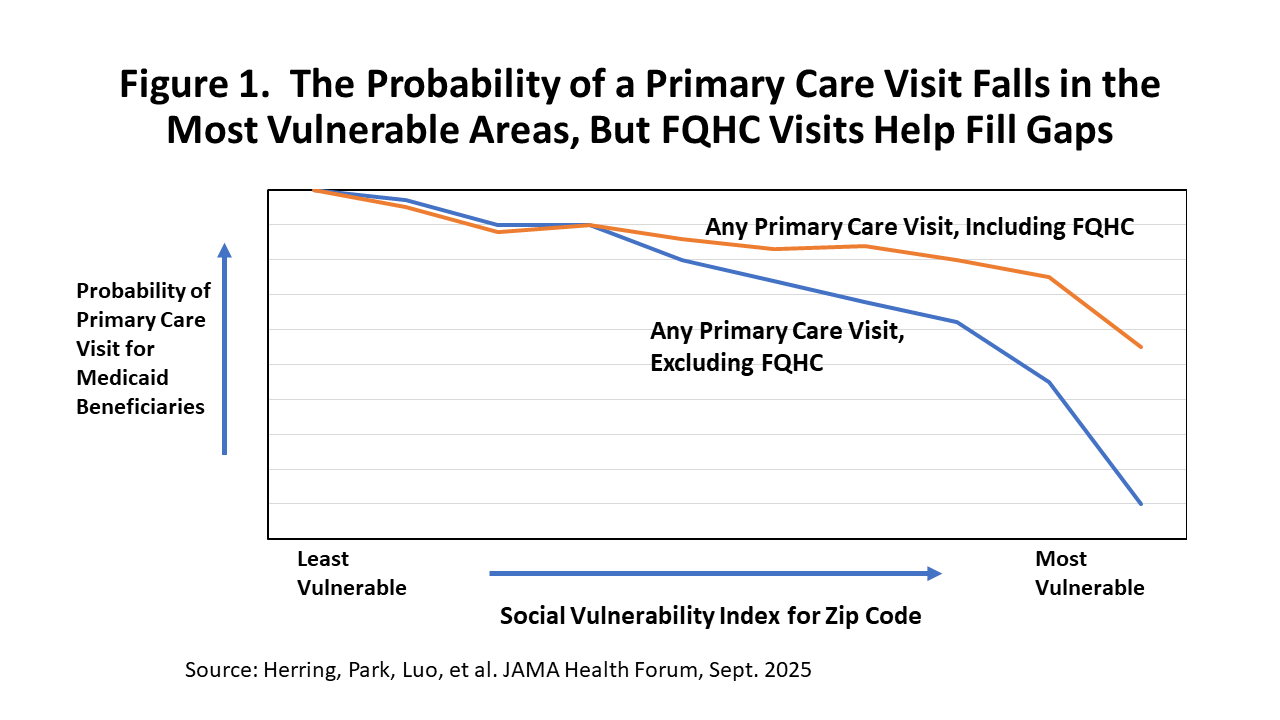

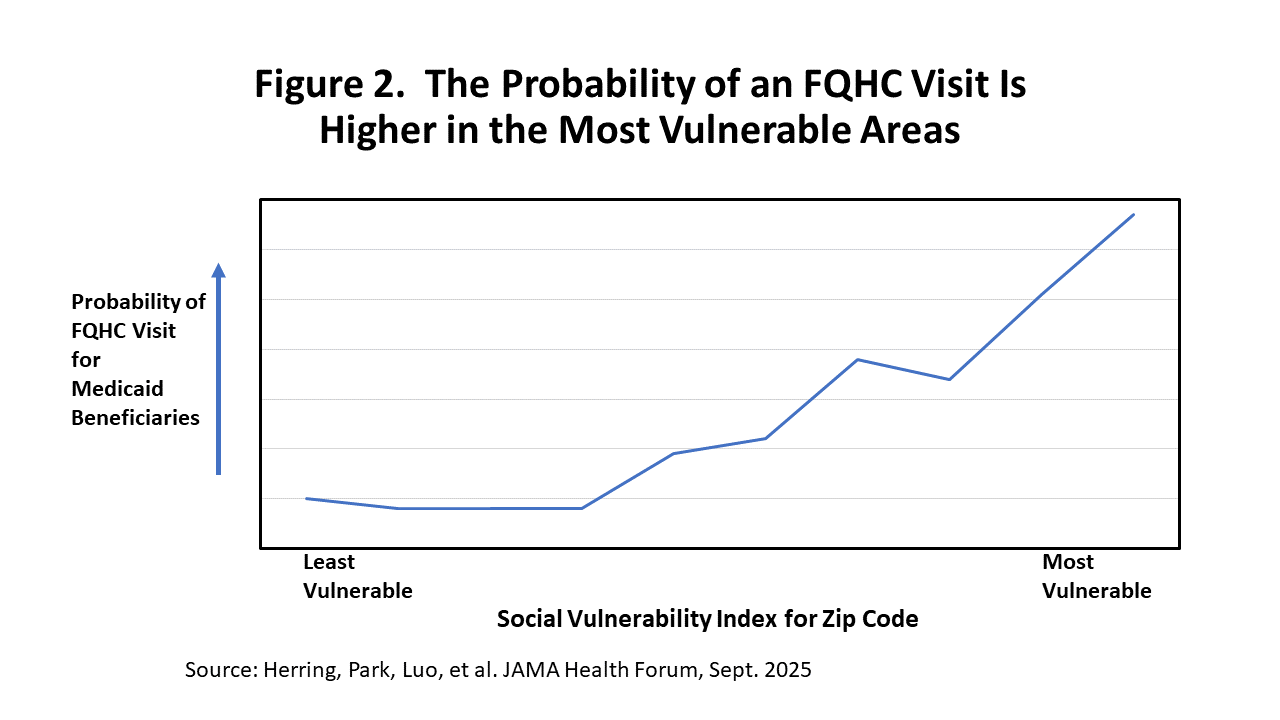

The research found that, in general, Medicaid patients who lived in the most socially disadvantaged zip codes were less likely to have a primary care visit, largely because there were not enough primary care physicians or other clinicians (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) practicing or caring for Medicaid patients in those areas. But the availability of FQHCs – which are located in areas that are medically underserved – counterbalanced those tendencies. Medicaid patients in those disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to get care at community health centers, which helped lift up access to care. That is, FQHCs helped fill the void left by the lack of other primary care providers in those communities. This demonstrates the success of community health centers in meeting health needs in the most vulnerable areas.

The researchers examined how likely Medicaid beneficiaries were to receive a primary care visit, based on the level of social disadvantage of the zip code where they lived, using the Social Vulnerability Index. The index, designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, measures neighborhoods’ needs, based on a composite of factors like degree of poverty, educational attainment, housing cost burden and insurance coverage. Not surprisingly, Medicaid beneficiaries are more likely to live in the socially vulnerable areas. Regrettably, however, those who lived in the most socially vulnerable areas (the lowest decile) were the least likely to have had a primary care visit, because of the limited availability of primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants) practicing in the area. But the fact that FQHCs are located in medically underserved areas means that they serve those in the most disadvantaged areas.

Figure 1 illustrates that the chance a Medicaid beneficiary gets a primary care visit is related to the social vulnerability of the community where they live. Because fewer primary care providers practice in the most vulnerable communities and there are more Medicaid beneficiaries, it becomes harder for Medicaid beneficiaries to receive primary care. This means they might go without care or turn to more expensive emergency rooms for care. But the difficulty finding primary care is alleviated in part when you add in the care provided at FQHCs.1

Figure 2 illustrates this in a different way, simply showing the probability that Medicaid beneficiaries have primary care visits at an FQHC, based on the social vulnerability of the area where they live. Medicaid beneficiaries are more likely to receive care at FQHCs in the most vulnerable areas, both because health centers are located in medically underserved areas and because not enough other primary care providers accept Medicaid in these areas. Thus, FQHCs become dominant and essential providers of primary care in the most vulnerable areas.

The researchers used detailed data about nearly 35 million Medicaid beneficiaries who were under the age of 65, as reported in the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) for 2019. They focused on the probability that a Medicaid patient received a primary care visit during the year. To assess who received primary care, they used an innovative “activity-based” measure that identifies health care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants) based on actual primary care services provided (e.g., check-ups, evaluation and management visits, etc.) to Medicaid patients, whether they worked at an FQHC or other primary care setting (e.g., a private doctor’s office or other outpatient setting).

Unfortunately, community health centers are facing financial headwinds. The most recent data, from 2024, indicate that most health centers are operating in the red. On average, revenues (from federal grants, Medicaid and other insurance) were 2.1% less than operational costs in 2024. Revenues are likely to fall even more in 2026, when the Affordable Care Act marketplaces lose ground due to the expiration of enhanced premium tax credits. Revenues will fall even further as Medicaid is deeply cut because of the recent One Big Beautiful Budget Act (Public Law 119-21). Current funding for the Section 330 grants that represent core funding for community health centers will expire on September 30, 2025 but Congress has not yet provided final appropriations.

Funding to support the expansion of health centers would allow them to do even more in providing access to primary care in the nation’s most disadvantaged communities.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

1. These analyses also control statistically for each person’s age and gender, and whether the person is disabled or is diagnosed with physical or mental disorders like diabetes or depression.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

About the Authors. Leighton Ku and Feygele Jacobs are faculty in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University and are affiliated with the Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health. Jordan Herring is a post-doctoral scholar in emergency medicine at Stanford Medical School and earned his PhD in public policy at George Washington University. His paper is based on work conducted with colleagues at the Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity at George Washington University.